4 Node.js Logging libraries which make sophisticated logging simpler

Node.js logging, like any form of software instrumentation, isn’t an easy thing to get right. It takes time, effort, and a willingness to continue to iterate until a proper balance is struck.

There are so many points to consider, including:

- How much information is too much?

- How much information is too little?

- What information should we store?

- What information should be omitted?

- What are the impacts of the logging protocols we choose?

Previously, here on the Loggly blog, I began exploring these questions in the context of three of the most popular web development languages: PHP, Python, and Ruby.

But these aren’t the only popular languages in use today. Node.js is another one that has widespread adoption. Given that, today I’m going to show you four logging libraries that make logging to Loggly from Node.js applications almost a breeze. They are:

Let’s start off with Node-Loggly.

Node-Loggly

Node-Loggly is fully compliant with the Loggly API, which covers sending data, searching data, and retrieving account information. The library can also log with tags and supports sending both shallow and complex JSON objects as the log message.

I’ve created a simple Node.js script, which shows how to make use of all of these features. Before stepping through it though, you’ll need to have a Loggly application token available, and the library source installed.

If you don’t have a token available, here’s how to both find and create one. To install the library, from the terminal, run:

npm install node-loggly bulk.

First, the Loggly library is included. Then we create a client object to handle the service interaction. Here, we need to provide the retrieved token and account subdomain.

With the client initialized, all that’s required to log a message is to call the log function on the client object, as below.

If, however, we want to be able to respond to events in the object’s life cycle, we can instead pass a callback function as the second argument, as I have done below. This will log the same message, and, if successful, log a confirmation message to STDOUT. Conversely, if something goes wrong, it will log that to STDOUT.

As I covered in the introduction, the library can log shallow or simple JSON objects as the message body. I’ve defined a shallow object below, which simply stores my name, employment, country, and languages that I’m proficient in.

To use the object as the message, we need to change how the client object is initialized, as shown below.

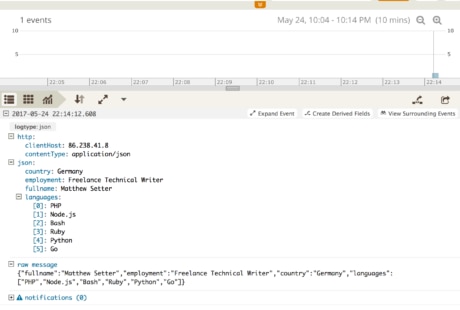

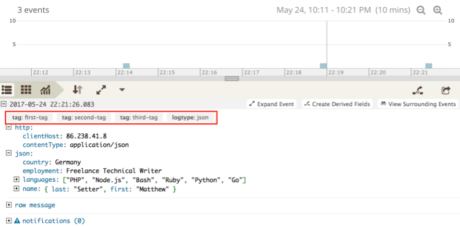

Now we can pass the object as the message, which results in the object being stringified, with a log message as depicted in the screenshot below.

But what about a complex object? A complex object, in essence, is an object that itself contains one or more nested objects, as in the example below. This is the same object as before. Instead of storing my name as a string, it stores it as two separate elements of a name object.

Passing this as the log message results in a similar message to the previous one, which you can see in this screenshot:

Node.js Logging with Tags

Tagging the messages we log, as in the screenshot below, requires no further change to how the client object is initialized.

In the code example below, in the object passed to the constructor, we’ve passed a tags element, which is an array of strings to tag the messages the clients log.

From these examples, you can see that the library provides a clean and simple interface, both for the createClientfunction and for the log call, to use to send log messages to our Loggly account. What it doesn’t do, which I’ve talked about previously, is to allow for more advanced functionality, such as custom formatting or configuration of custom logs for custom situations. However, the next two libraries do provide this functionality.

Winston

Winston has a larger, more robust feature set than Node-Loggly. It’s also the officially recommended setup on Loggly’s documentation for Node. With Winston, you can:

- Use multiple transports

- Create custom transports

- Perform profiling

- Handle exceptions

- Use one of a range of pre-defined error levels

- Create custom error levels

There’s more functionality than what I’ve covered here, so I can’t cover all of it today. I’ll instead focus on using custom transports and error levels. Here are the log priority levels available with Winston:

| Level | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Name | silly | debug | verbose | info | warn | error |

First we need to install Winston, which is done by running the command:

npm install winston

Next, here’s a basic logging example: In this example, we’ve initialized a Winston object; added a file transport, which will store logs in somefile.log; and then logged two messages at the level of info. The last two functions above are in effect the same. The last one is a utility function which reduces required code. If you run the code above, you’ll see the following appear in the console:

And if you tail somefile.log, you’ll see the following entries:

The reason for the console output is that by default, Winston loads a console transport. Let’s have a deeper look at transports by seeing how to add a Loggly transport. Specifically, we’re going to use Winston-Loggly Bulk, which we’ll install by running:

npm install winston-loggly-bulk

With that done, we first initialize a new Winston object, and add in support for Winston-Loggly-Bulk. So far, it’s largely the same as in the first example. Initializing logging this way has several advantages, which include:

- Being able to specify and configure multiple transports

- Specify the log priority level, above which the event will be passed along

In the example above, I’ve created a custom configuration, marking it as “development”. This uses two of the default transports, console and file. The console transport is configured to log any message with a priority from silly, the lowest, upwards.

As a further example of what’s possible, colorization of logs is also enabled, and a string, “category one”, will be prepended to all messages sent to the console.

The file transport is configured to log to the file we used previously and log any message with a priority level of warning or above.

Now what we’re going to do is to set up a range of loggers, based on various criteria, such as development environments, including development, staging, testing, and production.

In the above example, I’ve created a second custom logger, to be used in production. This one uses the Loggly transport, using a JSON object to specify the token and subdomain as we did in the previous Node-Loggly-Bulk example earlier.

Note: One other important point to note is that the name, “production”, will also be used as a tag on all messages logged with this logger!

Finally, we retrieve each logger configuration and log a message at the priority level info. Running this will log the following message to STDOUT but not to somefile.log, nor to Loggly.

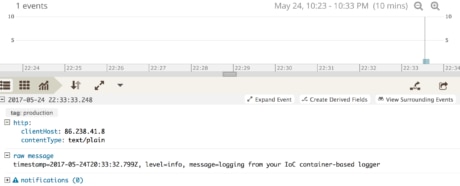

However, if we were to change the Loggly configuration options, to set the level to “silly,” then the message will also have been logged to Loggly, as in the screenshot below.

Bunyan

Let’s have a look at using Bunyan for logging to Loggly. Bunyan, like Winston, is a very feature-rich logging library, one used quite heavily by Joyent and many others for a number of production services.

But whereas Winston logs just the message by default, depending on the transport used, Bunyan also includes a process id (pid), hostname, and timestamp. It too can make use of custom transports, which it refers to as streams, to log data, based on a priority level. And it provides for the creation of custom loggers, based on specialization, such as development or production environment as we’ve created so far. As with Winston, we need to install Bunyan and the Loggly transport; the following command will take care of this.

npm install bunyan bunyan-loggly

Now let’s look at making use of it. We first initialize a new Bunyan object, then add the Bunyan-Loggly transport.

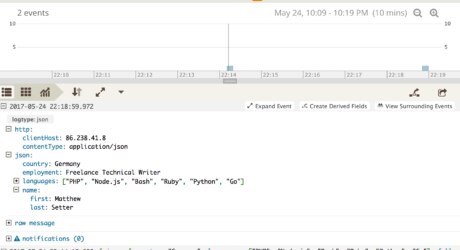

Similar to Winston, we create a new logger, called “my-logger”, then create a custom stream, named “logglylog”, of type raw, which will log messages to Loggly. We’ve initialized it with the token and subdomain as before, and specified “json” to true. This means that the message stream will be able to log JSON objects directly instead of stringifying them beforehand.

As in the earlier examples, I’ve created a compound object, which I’ll log at the info level, by calling the info function on the logger object, as below.

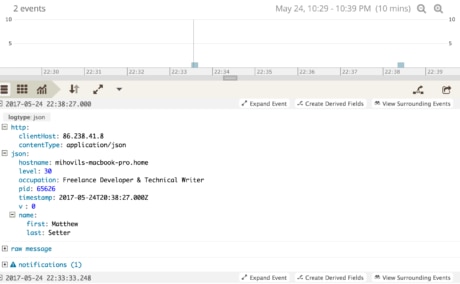

When we view it in the Loggly dashboard, it will have recorded the message we see below.

Child Loggers

Bunyan has a different approach to sub-categorizing loggers, using what it calls child loggers. What these do are extend the parent logger, effectively adding more context to the information which is logged. This is useful when you want to see all the logs from a given environment, from a given system component, or even to do transaction tracing. Let’s say that I want to write out the following log message, where you can see the environment’s been specified in the message.

To do that, I could create a new class, which creates a child logger from the parent logger which is passed to it in its constructor. In defining the child logger, it specifies a key of environment, with a value of development. This will customize the log message it writes, inserting the key/value pair. I’ve next defined a function on the class to log a message at the level of info.

Finally, we instantiate the object and call the method with a simple message about MySQL.

While it may not seem like a lot at first glance, using child loggers helps you identify a log message stream and thus forms a sort of trail or connection throughout the logs for a specific section of the application. The advantage of this approach is even bigger with Loggly Dynamic Field ExplorerTM, because in one click you can filter all of your logs to see the logs of that type.

Given that a lot of information can be stored, based on all kinds of criteria, child loggers make it easier to follow the information stored by a specific part or component of an application.

Morgan

Morgan is sometimes the most overlooked logging library because it is not as versatile or powerful as its previously mentioned competitors. But it fits one niche perfectly: Logging requests and/or responses in Express.js apps. This is because it is written as middleware. It’s also very easy to set up and use out of the box. Below is a simple example of using Morgan in an Express.js app.

Out of the box, there is no way to log to some other log storage source, such as a database or a service like Loggly. But if we look at the documentation a little bit, we can see that Morgan allows us to define an output stream.

This is our way to get the messages out of the app and into another service like Loggly. In the following example, we’ll see how we can do that by creating our own output stream class:

Now that we have a usable class, we just need to use it in our server startup script, as in the example below:

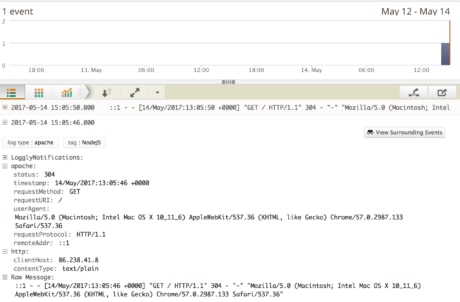

Now, if we run our app, we should see logs being sent and aggregated to Loggly via its web interface, as in the image below.

If you still find it limiting to use Morgan on its own, there is a way to combine other, more powerful loggers like Winston (also using the Loggly transport). You can learn more about this approach in the Ultimate Guide to Logging.

As you can see, Morgan is very simple to use but can be limiting. Fortunately, it is extensible through the use of streams and only has a small performance impact, which you can see in this benchmarking article by Lukas Rossi. As a result, it is a perfect choice for logging requests in areas such as web apps, audit logs, and debugging.

Wrapping Up

We’ve explored four great libraries for managing logging in Node.js applications. Each of them provides:

- Basic logging

- Specifying the minimum log level required before the log message will be passed on to be logged

- Custom log transports or streams for tracking activity across a range of log messages, as Bunyan does with child logs

- Useful presets to save you from repetitive coding

As a result they’re robust logging solutions.

They can’t, by themselves, however, answer the questions we’ve been exploring of late, specifically the ones I raised at the start of the article. Those are questions for you and your development team.

But as we’ve started to see in the code samples we worked through, they have the functionality needed for implementing anything from the most basic, to more advanced logging practices, practices that in effect help implement the answers to these questions.

For example, we can approach the following four questions with priority levels and child loggers:

- What information should be omitted?

- How much is too much?

- How much is too little?

- What information should we store?

Using these two aspects of functionality allows for nearly anything to be logged in code. Then, when the code runs, messages not considered important in that environment can be automatically filtered out.

Some environments require more information or more specialized information, while others require less. Child loggers provide a mature solution to this problem, one that’s easily implemented and maintained. These are just a few of the ways in which the functionality of these libraries answers these questions. Can you identify others?

Start logging to Loggly from your Node.js applications in minutes.

Click to sign-up for a free 14 day log analysis account.

If you’d like to know more about Bunyan, check out this excellent presentation by Trent Mick at Joyent, or the repository documentation. If you’d like to know more about Winston, check out the repository documentation and for Morgan, check its repository documentation.

Node.js Logging Libraries In Use

Want to see node.js log analysis in action? Check out my video!

The Loggly and SolarWinds trademarks, service marks, and logos are the exclusive property of SolarWinds Worldwide, LLC or its affiliates. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Matthew Setter